Analytical Vignette #1

Franz Schubert, Piano Sonata No. 13 in A Major, Op. 120 (D664), II-Andante

Example 1: First statement of appoggiature motive (mm. 1–2)

Example 1: First statement of appoggiature motive (mm. 1–2)

1. Introduction

In the summer of 1819 22-year-old Franz Schubert went on the first of what would become almost yearly sojourns to the Austrian countryside, “making extended stops in both Steyr and Linz” with friend and musical collaborator baritone Johann Michael Vogl.[1] It was during this relaxed and presumably happy trip that Schubert composed two equally cheerful works: the famous “Trout” Quintet, D667, and his first mature piano sonata, No. 13 in A Major, D664.[2] Indeed, in a review of a Oliver Schnyder’s 2001 recording of the sonata, Jerry Dubins describes the character of the first movement as having an “insouciant innocence…like an easygoing amble down a country lain lined by peaceful meadows.”[3] The second movement, an Andante as is so typical of Classical and Romantic piano sonata and symphony second movements, also projects an air of content wandering. Although the content of the remainder of this analytical vignette is somewhat loosely strung together, this historical context and description of the general mood of the piano sonata serves as a backdrop to tie things together. Here is a PDF of the score in question and here is a link to a lovely performance by Claudio Arrau.

2. Retroactive Correction of Tonal Problems

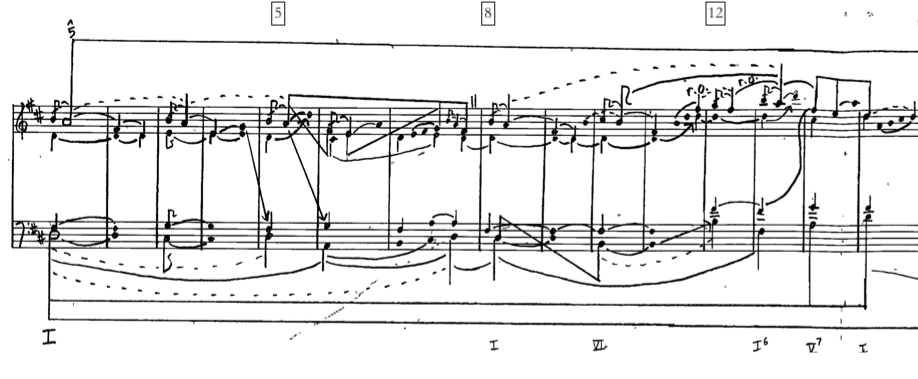

A musical narrative asserts itself at the very beginning of the movement and reappears at various hierarchical levels no less than four other times: the retroactive correction of tonal problems. Example 1, the piece’s opening bar, shows the seed of this dramatic theme. Schubert writes an appoggiatura B4 in the top voice and its double B3 in the tenor register on the downbeat which resolves to chord tone A’s for beats two and three (I will henceforth refer to this as the “appoggiatura motive;” more on this motive in section 3). The two sonorities in the measure are both stable to some extent—i.e., both the B minor 6/3 chord and the D major 5/3 chord contain pitches which are all consonant with each other—but it is hard to hear the former as more stable or hierarchically superordinate to the latter. It would be unusual to start a movement on a triad in first inversion, especially given that this piece was composed almost in Classical era territory, chronologically speaking. Within this measure, then, we see a tonal problem being retroactively fixed on the very small scale of just two beats. At first an unexpected harmony is stated (even accented metrically and given a diminuendo after its articulation by Schubert) and then beats two–three of m. 1 serve to fix this sonority, or perhaps provide the truly intended harmony. See Example 2 for a Schenkerian foreground graph of mm. 1–15, the A section, in which I interpret this first B4 in the top voice as an incomplete upper neighbor to A4.

In the summer of 1819 22-year-old Franz Schubert went on the first of what would become almost yearly sojourns to the Austrian countryside, “making extended stops in both Steyr and Linz” with friend and musical collaborator baritone Johann Michael Vogl.[1] It was during this relaxed and presumably happy trip that Schubert composed two equally cheerful works: the famous “Trout” Quintet, D667, and his first mature piano sonata, No. 13 in A Major, D664.[2] Indeed, in a review of a Oliver Schnyder’s 2001 recording of the sonata, Jerry Dubins describes the character of the first movement as having an “insouciant innocence…like an easygoing amble down a country lain lined by peaceful meadows.”[3] The second movement, an Andante as is so typical of Classical and Romantic piano sonata and symphony second movements, also projects an air of content wandering. Although the content of the remainder of this analytical vignette is somewhat loosely strung together, this historical context and description of the general mood of the piano sonata serves as a backdrop to tie things together. Here is a PDF of the score in question and here is a link to a lovely performance by Claudio Arrau.

2. Retroactive Correction of Tonal Problems

A musical narrative asserts itself at the very beginning of the movement and reappears at various hierarchical levels no less than four other times: the retroactive correction of tonal problems. Example 1, the piece’s opening bar, shows the seed of this dramatic theme. Schubert writes an appoggiatura B4 in the top voice and its double B3 in the tenor register on the downbeat which resolves to chord tone A’s for beats two and three (I will henceforth refer to this as the “appoggiatura motive;” more on this motive in section 3). The two sonorities in the measure are both stable to some extent—i.e., both the B minor 6/3 chord and the D major 5/3 chord contain pitches which are all consonant with each other—but it is hard to hear the former as more stable or hierarchically superordinate to the latter. It would be unusual to start a movement on a triad in first inversion, especially given that this piece was composed almost in Classical era territory, chronologically speaking. Within this measure, then, we see a tonal problem being retroactively fixed on the very small scale of just two beats. At first an unexpected harmony is stated (even accented metrically and given a diminuendo after its articulation by Schubert) and then beats two–three of m. 1 serve to fix this sonority, or perhaps provide the truly intended harmony. See Example 2 for a Schenkerian foreground graph of mm. 1–15, the A section, in which I interpret this first B4 in the top voice as an incomplete upper neighbor to A4.

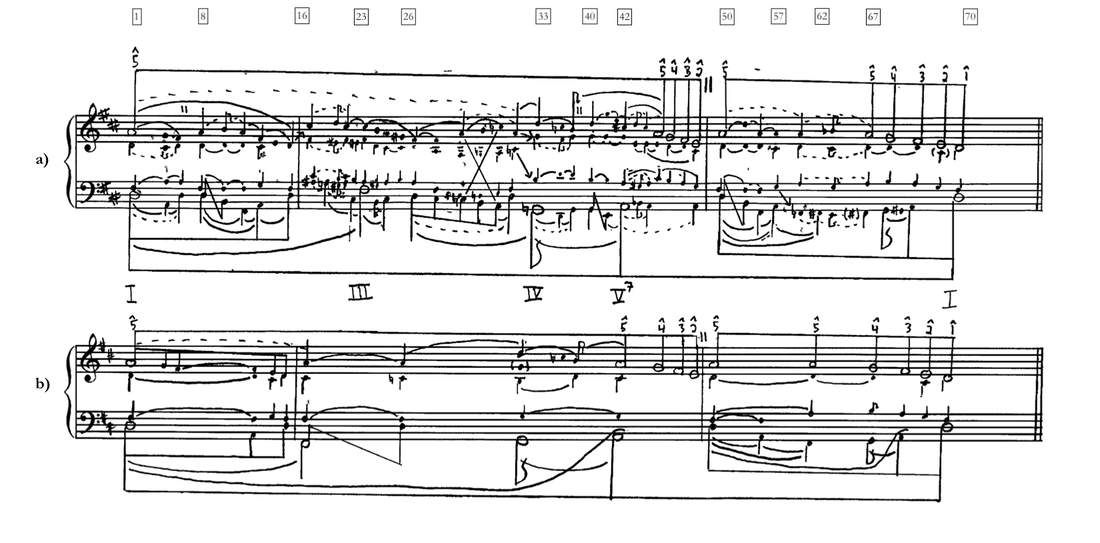

Examples 3a–b: Middleground and deep middleground sketches of entire movement

Examples 3a–b: Middleground and deep middleground sketches of entire movement

On a slightly larger scale (over the course of two measures), the deceptive resolution of what appears to be the first cadential progression in m. 6 is corrected in m. 7. The appoggiatura motive appears again in m. 6, this time delaying a V7 chord (the F♯in the soprano is suspended from an inner voice in m. 5, shown as an unfolding in Example 2). Instead of resolving to an expected tonic chord, however, the bass moves up to B2, providing a true B minor triad an another tonal problem: a deceptive cadence. Of course, the bass continues to rise over the course of m. 7, arriving at C# (construed in Example 2 as an upper third of the A from m. 6) supporting an inverted dominant 7th chord and ultimately resolving to the tonic triad; m. 7 both retroactively corrects the deceptive resolution of m. 6–7 and creates a different tonal problem in that the V65 chord provides a weakened cadence (Caplin would not consider m. 7 a cadence at all because of the lack of motion from a root position dominant to a root position tonic[4]), putting into question the identity of mm. 1–7 as a closed phrase.

Once again increasing our temporal scope, another manifestation of the tonal correction narrative over mm. 16–19. After a Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC) in m. 15, Schubert moves to what initially sounds like a V6/5 of vi (B minor) in m. 16. The function of the chord in m. 16, however, is recontextualized and therefore warrant aural and analytical reinterpretation by the C♯dominant 7th chord in second inversion in m. 17. The latter chord retroactively makes the m. 16 sound like a (at least temporary) tonic chord in first inversion. The F♯minor triad in first inversion in m. 18 and the cadential progression that follows from mm. 20–23 confirms the tonicization of F♯minor, and thus m. 17 and following retroactively correct the meaning of the chord in m. 16. “Correct” is a somewhat misplaced word here since there is nothing unusual or wrong with a secondary dominant of the relative minor after a tonic-confirming cadence at the end of the first section of a piece. Retroactive reinterpretation is probably more suitable. The Schenkerian graphs in Examples 3a–b and 7 (the latter willbe discussed in more detail in section 4) both show dotted slurs from the bass’s A♯of m. 16 to the A natural in m. 18, thus interpreting m. 16 as a modally mixed temporary tonic in F♯minor.

The fourth manifestation of the retroactive correction trope plays out on the largest scale yet: over the course of the entire B section, i.e., mm. 16–49. As just discussed, this passage begins with a tonicization of F♯minor, the mediant key in the movement’s tonic of D major. This would not be a totally unusual key to control a contrasting section in the year 1819, but it is certainly not the “most normal” (the dominant, subdominant, or submediant being more prototypical). And, as we have already seen, Schubert arrives at F♯minor via a back door modal mixture reinterpretation of what originally seemed to be a secondary dominant in m. 16. Furthermore, when the B section tries to confirm the key of F♯minor via a cadence, it gets stuck. First, there is a “retry” when mm. 20–21 are repeated nearly verbatim in mm. 23–25. Second, after the cadential 6/4 in m. 25 resolves to a dominant 7th chord (missing a leading tone in F♯), it resolves deceptively to VI in F♯minor, harkening back to the harmonic motion in the global tonic over mm. 6–7 where V7 of D major resolved deceptively to vi. Something is amiss. The bass’s return to C♯in mm. 28–29 is not a confident sign that F♯minor is in control because of how drawn out the harmonic rhythm is from mm. 26–29. Indeed, we soon find the bass slipping down and the upper voice creeping chromatically, fully threatening F♯minor’s stance as the key of the B section. Finally, the almost out-of-nowhere arrival of G major in mm. 32–33 via a full cadential progression and a PAC that elides with the beginning of a varied statement of the opening theme in m. 33 provides dramatic resolution. G major’s emergence as “the key” of the B section retroactively corrects the tenuous and less-prototypical role F# minor played. This is not to say that the piece is better onlywhen G major arrives. Schubert is surely playing with norms and expectations here, and it is his interesting reworking of the chord in m. 16 as well as the dissolution of F# minor just when it was about to cadence—both retroactive corrections of tonal problems—that makes G major and the remainder of the B section feel all the more emphatic, proud, and joyous, not to mention the piece as a whole a more interesting work of art.

Finally, as the Schubert retroactively corrects a very weakly supported in the Urlinie approaching the interruption at m. 50 with a strongly supported scale-degree 4 (^4) in m. 68. This is demonstrated in Example 3b, where the top voice approaching the interruption descends from ^5 to ^2 after the arrival of the structural dominant. Thus, ^4 is a dissonant passing tone, receiving no harmonic support, and little contrapuntal or metric support. However, in the A’ section, ^4 receives very solid harmonic support: in Example 3b, the bass has a flagged G and in m. 68 of the score, a G major harmony is quite obviously projected. This retroactive correction of tonal problems is the longest range one in the piece, and, indeed, it might not be audible without careful study from a Schenkerian perspective. But I think it invite a performer to celebrate the G major harmony in m. 68, perhaps emphasizing dynamically and through rubato just as much as one would with the V chord of m. 69.

Once again increasing our temporal scope, another manifestation of the tonal correction narrative over mm. 16–19. After a Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC) in m. 15, Schubert moves to what initially sounds like a V6/5 of vi (B minor) in m. 16. The function of the chord in m. 16, however, is recontextualized and therefore warrant aural and analytical reinterpretation by the C♯dominant 7th chord in second inversion in m. 17. The latter chord retroactively makes the m. 16 sound like a (at least temporary) tonic chord in first inversion. The F♯minor triad in first inversion in m. 18 and the cadential progression that follows from mm. 20–23 confirms the tonicization of F♯minor, and thus m. 17 and following retroactively correct the meaning of the chord in m. 16. “Correct” is a somewhat misplaced word here since there is nothing unusual or wrong with a secondary dominant of the relative minor after a tonic-confirming cadence at the end of the first section of a piece. Retroactive reinterpretation is probably more suitable. The Schenkerian graphs in Examples 3a–b and 7 (the latter willbe discussed in more detail in section 4) both show dotted slurs from the bass’s A♯of m. 16 to the A natural in m. 18, thus interpreting m. 16 as a modally mixed temporary tonic in F♯minor.

The fourth manifestation of the retroactive correction trope plays out on the largest scale yet: over the course of the entire B section, i.e., mm. 16–49. As just discussed, this passage begins with a tonicization of F♯minor, the mediant key in the movement’s tonic of D major. This would not be a totally unusual key to control a contrasting section in the year 1819, but it is certainly not the “most normal” (the dominant, subdominant, or submediant being more prototypical). And, as we have already seen, Schubert arrives at F♯minor via a back door modal mixture reinterpretation of what originally seemed to be a secondary dominant in m. 16. Furthermore, when the B section tries to confirm the key of F♯minor via a cadence, it gets stuck. First, there is a “retry” when mm. 20–21 are repeated nearly verbatim in mm. 23–25. Second, after the cadential 6/4 in m. 25 resolves to a dominant 7th chord (missing a leading tone in F♯), it resolves deceptively to VI in F♯minor, harkening back to the harmonic motion in the global tonic over mm. 6–7 where V7 of D major resolved deceptively to vi. Something is amiss. The bass’s return to C♯in mm. 28–29 is not a confident sign that F♯minor is in control because of how drawn out the harmonic rhythm is from mm. 26–29. Indeed, we soon find the bass slipping down and the upper voice creeping chromatically, fully threatening F♯minor’s stance as the key of the B section. Finally, the almost out-of-nowhere arrival of G major in mm. 32–33 via a full cadential progression and a PAC that elides with the beginning of a varied statement of the opening theme in m. 33 provides dramatic resolution. G major’s emergence as “the key” of the B section retroactively corrects the tenuous and less-prototypical role F# minor played. This is not to say that the piece is better onlywhen G major arrives. Schubert is surely playing with norms and expectations here, and it is his interesting reworking of the chord in m. 16 as well as the dissolution of F# minor just when it was about to cadence—both retroactive corrections of tonal problems—that makes G major and the remainder of the B section feel all the more emphatic, proud, and joyous, not to mention the piece as a whole a more interesting work of art.

Finally, as the Schubert retroactively corrects a very weakly supported in the Urlinie approaching the interruption at m. 50 with a strongly supported scale-degree 4 (^4) in m. 68. This is demonstrated in Example 3b, where the top voice approaching the interruption descends from ^5 to ^2 after the arrival of the structural dominant. Thus, ^4 is a dissonant passing tone, receiving no harmonic support, and little contrapuntal or metric support. However, in the A’ section, ^4 receives very solid harmonic support: in Example 3b, the bass has a flagged G and in m. 68 of the score, a G major harmony is quite obviously projected. This retroactive correction of tonal problems is the longest range one in the piece, and, indeed, it might not be audible without careful study from a Schenkerian perspective. But I think it invite a performer to celebrate the G major harmony in m. 68, perhaps emphasizing dynamically and through rubato just as much as one would with the V chord of m. 69.

Example 4: Varied iteration of the appoggiature motive in (mm. 24–28)

Example 4: Varied iteration of the appoggiature motive in (mm. 24–28)

3. Motivic and Associative Play

Schubert–working contemporaneously with Beethoven whose music is often centered on constant motivic repetition and variation (e.g., Op. 2, No. 1, first movement and the opening movement of the 5th Symphony)–creates coherence in this movement via motivic repetition and recontextualization, variation, and associative play. The appoggiatura motive is present in its original metrical setting (non-chord or unstable tone on the first beat followed by the chord or stable tone on beats two and three) and in some version of its original melodic contour (descent by step) in 40 out of the 75 measures of this movement. In a couple of cases, Schubert changes the harmonic context and melodic behavior of the motive such that it is notably different in tonal content from the first iteration in m. 1. For example, in m. 27, the motive appears in melodic inversion (ascending step) in the tenor voice (G♯–A; see Example 4). The metrical setting and rhythm are retained, but in addition to the melodic inversion, G♯ and A are equally likely candidates for being chord members, a.k.a, the “stable” note. M. 27 is an augmented 6th chord in F♯minor, and if whether G♯or A are taken as the main note in the tenor, the harmonic function remains the same; only the flavor (a French vs. a German augmented 6th) is changed. Another notable variation is the descending melodic leaps (minor 3rds) that take place in mm. 30–31 instead of the original descending steps. The use of descending 3rds instead of 2nds returns in the retransition when the dominant lock has arrived (see mm. 46–49). Furthermore, the note A4 sounded on the downbeats of these two bars is a chord member in both measures. The pitch class A is literally sounded in a tenor voice (A3) in both mm. 30 and 31. Nonetheless, this recontextualization and melodic variation of the appoggiatura motive is quite fitting: remember that at this point in the movement, we are breaking away from the turbulence caused by F♯minor and approaching the repose and resolution afforded by the G major passage. This the physical effort projected by vertically stretching out the motive reflects the yearning for tonal change; this tonal change, of course, does actually happen starting at m. 32.

Long before Schubert, composers and performers engaged in various methods of varying repeated sections of music. For example, in da capo arias from the Baroque through the Classical eras, singers were expected to add embellishments to the second statement of the first section of the aria (I’m talking here about variations occurring in the A’ section in an ABA’ model). In the movement in question here, Schubert plays with the appoggiatura motive at the return of the A section (mm. 50 ff.) to increase the energy of the piece and avoid restating mm. 1–15 exactly. Here, motivic density is increased in two ways. First of all, note that the left hand looks different over mm. 50–54 than the corresponding mm. 1–5. Instead of doubling the top voice in octaves with a tenor range voice, Schubert sets the two voices in imitation starting at m. 50. Thus, while we had a statement of the appoggiatura motive once every two measures from mm. 1–5, we hear it in every bar from mm. 50–54. The second way motivic density is increase here is by a truncation of the material from mm. 1–15. Remember that m. 6–7 (corresponding to mm. 55–56) contained a composed out V7–I resulting in a point of repose (almost cadence) at the end of m. 7. In m. 55, however, Schubert thwarts our expectations for a V7 in m. 55 by “skipping” to what was originally m. 10. Furthermore, m. 56 is m. 14, another truncation of the original A section. This all results in an increased motivic density: while we heard the appoggiatura motive nine times over mm. 1–15 (fifteen bars), we hear it ten times over mm. 50–59 (ten bars).

Schubert–working contemporaneously with Beethoven whose music is often centered on constant motivic repetition and variation (e.g., Op. 2, No. 1, first movement and the opening movement of the 5th Symphony)–creates coherence in this movement via motivic repetition and recontextualization, variation, and associative play. The appoggiatura motive is present in its original metrical setting (non-chord or unstable tone on the first beat followed by the chord or stable tone on beats two and three) and in some version of its original melodic contour (descent by step) in 40 out of the 75 measures of this movement. In a couple of cases, Schubert changes the harmonic context and melodic behavior of the motive such that it is notably different in tonal content from the first iteration in m. 1. For example, in m. 27, the motive appears in melodic inversion (ascending step) in the tenor voice (G♯–A; see Example 4). The metrical setting and rhythm are retained, but in addition to the melodic inversion, G♯ and A are equally likely candidates for being chord members, a.k.a, the “stable” note. M. 27 is an augmented 6th chord in F♯minor, and if whether G♯or A are taken as the main note in the tenor, the harmonic function remains the same; only the flavor (a French vs. a German augmented 6th) is changed. Another notable variation is the descending melodic leaps (minor 3rds) that take place in mm. 30–31 instead of the original descending steps. The use of descending 3rds instead of 2nds returns in the retransition when the dominant lock has arrived (see mm. 46–49). Furthermore, the note A4 sounded on the downbeats of these two bars is a chord member in both measures. The pitch class A is literally sounded in a tenor voice (A3) in both mm. 30 and 31. Nonetheless, this recontextualization and melodic variation of the appoggiatura motive is quite fitting: remember that at this point in the movement, we are breaking away from the turbulence caused by F♯minor and approaching the repose and resolution afforded by the G major passage. This the physical effort projected by vertically stretching out the motive reflects the yearning for tonal change; this tonal change, of course, does actually happen starting at m. 32.

Long before Schubert, composers and performers engaged in various methods of varying repeated sections of music. For example, in da capo arias from the Baroque through the Classical eras, singers were expected to add embellishments to the second statement of the first section of the aria (I’m talking here about variations occurring in the A’ section in an ABA’ model). In the movement in question here, Schubert plays with the appoggiatura motive at the return of the A section (mm. 50 ff.) to increase the energy of the piece and avoid restating mm. 1–15 exactly. Here, motivic density is increased in two ways. First of all, note that the left hand looks different over mm. 50–54 than the corresponding mm. 1–5. Instead of doubling the top voice in octaves with a tenor range voice, Schubert sets the two voices in imitation starting at m. 50. Thus, while we had a statement of the appoggiatura motive once every two measures from mm. 1–5, we hear it in every bar from mm. 50–54. The second way motivic density is increase here is by a truncation of the material from mm. 1–15. Remember that m. 6–7 (corresponding to mm. 55–56) contained a composed out V7–I resulting in a point of repose (almost cadence) at the end of m. 7. In m. 55, however, Schubert thwarts our expectations for a V7 in m. 55 by “skipping” to what was originally m. 10. Furthermore, m. 56 is m. 14, another truncation of the original A section. This all results in an increased motivic density: while we heard the appoggiatura motive nine times over mm. 1–15 (fifteen bars), we hear it ten times over mm. 50–59 (ten bars).

Example 6: J.S. Bach, four-part chorale setting of "Nun rune all Wälder"

Example 6: J.S. Bach, four-part chorale setting of "Nun rune all Wälder"

Another fascinating way that Schubert plays with motivic repetition and recontextualization is shown in the annotated score excerpt in Example 5. The figures beneath the score refer to intervals above the lowest voice and demonstrate that Schubert cycles the appoggiatura motive through each of the normal upper voice suspension-resolution actions one learns in traditional counterpoint: 6–5, 7–6, 9–8, and 4–3. On the musical surface, these are appoggiaturas, not true suspensions since no voice literally ties the unstable notes over the barline, which is why I call them “suspension actions.” Quite interestingly, while these suspension actions occur as one-voice phenomena in the A section, the A’s section (mm. 50–end) makes more use of multi-voice suspension actions. For example, m. 55 makes use of a 9–8 and a 4–3 simultaneously. Similarly, m. 57 contains a 6–5 and a 4–3. This adds to the variety and heightened drama of the A’ section described the in the preceding paragraph.

One final form of motivic/associative play that I’d like to draw out here involves what Milton Babbitt called “associative harmonies.”[5] This partially compositional partially cognitive phenomenon is demonstrated quite readily in one of J.S. Bach’s four-part chorales, a setting of “Num ruhen alle Wälder,” displayed here at Example 6. One of the most expressive moments in the chorale is the IV6/5 chord that serves as the structural predominant in the final phrase (m. 12, beat one). In a way, this chord arises out of voice leading more than out of vertical chordal logic since the C (the chordal 7th that gives this sonority its tasty dissonance) is an accented passing tone in the melody. Nonetheless, our ears have been primed to hear this chord as more than a voice-leading chord because the very same collection of pitches sounded as a predominant harmony on the downbeat of m. 2 (although there in second inversion). Even as early as the downbeat of m. 1, Bach hints at a major-major 7th chord on D♭ by sounding the pitches D♭–F–A♭–C for just an instant when the bass passes through an eighth note C4 on the second half of the beat. There is much less of a case to be made for calling that instance a “IV4/2,” but the associative function is still present.

Associative harmonies like those found in “Nun ruhen alle Wälder” serve to add coherence, a sense of familiarity, and accessibility to musical works, and Schubert employs them in such a manner to great effect in D664, mvt. II. The opening sonority of the piece (the B minor 6/3) is, of course, hierarchically subordinate to the D major 5/3 in the second two-thirds of m. 1. But this is does not mean that it doesn’t play an expressive role throughout the piece. In fact I argue that this B minor chord is an associative harmony, crucial to the beauty and logic of the movement. First, note the relation between the opening B minor triad and the deceptive resolution of the dominant 7th chord from mm. 6–7. The downbeat of m. 7 is somewhat surprising, but it is tied back aurally to the first sound of the piece, and therefore seems to make more sense. Second, where does the already-discussed F♯6/3 chord in m. 16 come from? Yes, this triad is recontextualized via modal mixture in m. 18, but reading from left to right, I think the fact that a secondary dominant of B (and probably B minor given the key signature) is made all the more sensible because the very first sound we here in the movement if a B minor chord. Much more could certainly be said about the motivic play and association at work in this movement, but hopefully the above observations can enrich our hearing and performance of the work.

One final form of motivic/associative play that I’d like to draw out here involves what Milton Babbitt called “associative harmonies.”[5] This partially compositional partially cognitive phenomenon is demonstrated quite readily in one of J.S. Bach’s four-part chorales, a setting of “Num ruhen alle Wälder,” displayed here at Example 6. One of the most expressive moments in the chorale is the IV6/5 chord that serves as the structural predominant in the final phrase (m. 12, beat one). In a way, this chord arises out of voice leading more than out of vertical chordal logic since the C (the chordal 7th that gives this sonority its tasty dissonance) is an accented passing tone in the melody. Nonetheless, our ears have been primed to hear this chord as more than a voice-leading chord because the very same collection of pitches sounded as a predominant harmony on the downbeat of m. 2 (although there in second inversion). Even as early as the downbeat of m. 1, Bach hints at a major-major 7th chord on D♭ by sounding the pitches D♭–F–A♭–C for just an instant when the bass passes through an eighth note C4 on the second half of the beat. There is much less of a case to be made for calling that instance a “IV4/2,” but the associative function is still present.

Associative harmonies like those found in “Nun ruhen alle Wälder” serve to add coherence, a sense of familiarity, and accessibility to musical works, and Schubert employs them in such a manner to great effect in D664, mvt. II. The opening sonority of the piece (the B minor 6/3) is, of course, hierarchically subordinate to the D major 5/3 in the second two-thirds of m. 1. But this is does not mean that it doesn’t play an expressive role throughout the piece. In fact I argue that this B minor chord is an associative harmony, crucial to the beauty and logic of the movement. First, note the relation between the opening B minor triad and the deceptive resolution of the dominant 7th chord from mm. 6–7. The downbeat of m. 7 is somewhat surprising, but it is tied back aurally to the first sound of the piece, and therefore seems to make more sense. Second, where does the already-discussed F♯6/3 chord in m. 16 come from? Yes, this triad is recontextualized via modal mixture in m. 18, but reading from left to right, I think the fact that a secondary dominant of B (and probably B minor given the key signature) is made all the more sensible because the very first sound we here in the movement if a B minor chord. Much more could certainly be said about the motivic play and association at work in this movement, but hopefully the above observations can enrich our hearing and performance of the work.

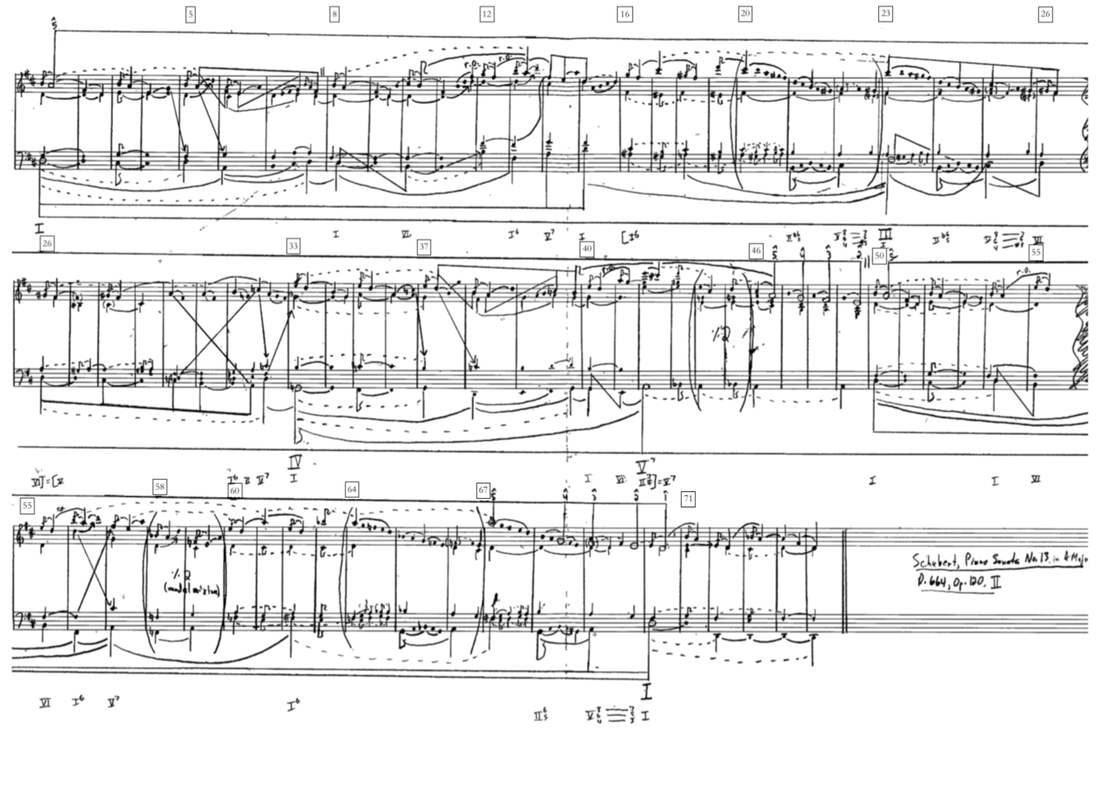

Example 7: Foreground sketch of entire movement

Example 7: Foreground sketch of entire movement

4. Schenkerian Interpretation

Much of this piece is relatively straightforward in terms of a Schenkerian analysis. Refer, again, to Examples 3a–b and 7 (displayed here) for middleground and foreground sketches, respectively, of the entire movement. Here I will discuss just two matters of Schenkerian interpretation of the piece that were, for me, less than straightforward: the passage from mm. 26–33 and the larger-scale interpretation of the motion to F♯minor then G major before the interruption on ^2 supported by V at m. 49.

My interpretation of mm. 26–33 is essentially V–I in G major with the D composed out through a fourth progression from mm. 26–32. The reason I bring up this passage as problematic is because, like so many Schenkerian analyses, it feels counterintuitive to say that the D in m. 26 is the same as the D in m. 32. First of all, a number of unstable harmonies temporally separate the two and, secondly, the D major triad in m. 26 has—in context—a VI-ness to it, while the D7 of m. 32 is undeniably a dominant 7th acting like a dominant 7th. Nonetheless, there is a strong case to be made for the arpeggiation of the D to its upper fifth/lower fourth A. First, the slowing of the harmonic rhythm at m. 26 allows our ears to sit on the D major sound momentarily and give a chance to break away from an F♯minor context. Second, the repeated anacrusic rhythm of the melody in mm. 30–31 creates momentum that propels the music—including the voice-leading and harmony—forward; thus the C♮ of m. 30 and the B of m. 31 are more convincingly participating in a fourth progression because of the forward momentum of the top voice.

As shown most clearly in Examples 3a and b, my large scale interpretation of the first half of the piece treats the F♯minor section as an upper third of D (with the voice on D moving down by step, a Leittonweschel) and the G major section as the structural predominant, a lower neighbor to the structural dominant A, which arrives in m. 42. This allows for a melodic (and Classical, with a capital ‘C’) bass: ^1–^3–^4–^5–^1. If Mozart wrote this piece, it would probably support the cadential progression I–I6–II6/5–V6/4–V7–I but here, ^1–^3–^4–^5–^1 supports I–III–IV–V7–I. The most striking aspect of this (which, again, speaks to the sometimes counterintuitive nature of Schenkerian readings) is the role of F♯. When we listen to or perform this piece, I think few of us are thinking “O.K., I’m really composing out D major by prolonging its upper third with one voice lowered by step” from mm. 16–26. Rather, I think most of us would just say “I’m in F♯minor right now, cool.” But Schenkerian analysis demands hierarchical relegation within a diatonic framework. And if we do take F♯as the upper third of D, then it is the amount of temporal and tonal emphasis given to that F♯that is striking. This knowledge might suggest that a performer could play more tentatively from mm. 16–26, walking on eggshells instead of breathing Austrian countryside air like you might in mm. 1–15.

SGP–June, 2019

Footnotes:

[1]Maurice J.E. Brown, Eric Sams, and Robert Winter, “Schubert, Franz,” Grove Music Online (2001), accessed 29 May, 2019, https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000025109.

[2]Ibid.

[3]Jerry Dubins, “Schubert: Piano Trio in E♭, op. 100. Piano Sonata in A, op. 120 (D. 664),” Fanfare 34, no. 5 (May–June, 2011), 392–3.

[4]Willian Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

[5]See Milton Babbitt, The Collected Essays of Milton Babbitt, ed. Stephen Dembski, Andrew Mead, and Joseph N. Straus (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011) and Joseph N. Straus, “Babbitt the Analyst,” Music Theory Spectrum 34, no. 1 (Spring, 2012), 26–33.

Much of this piece is relatively straightforward in terms of a Schenkerian analysis. Refer, again, to Examples 3a–b and 7 (displayed here) for middleground and foreground sketches, respectively, of the entire movement. Here I will discuss just two matters of Schenkerian interpretation of the piece that were, for me, less than straightforward: the passage from mm. 26–33 and the larger-scale interpretation of the motion to F♯minor then G major before the interruption on ^2 supported by V at m. 49.

My interpretation of mm. 26–33 is essentially V–I in G major with the D composed out through a fourth progression from mm. 26–32. The reason I bring up this passage as problematic is because, like so many Schenkerian analyses, it feels counterintuitive to say that the D in m. 26 is the same as the D in m. 32. First of all, a number of unstable harmonies temporally separate the two and, secondly, the D major triad in m. 26 has—in context—a VI-ness to it, while the D7 of m. 32 is undeniably a dominant 7th acting like a dominant 7th. Nonetheless, there is a strong case to be made for the arpeggiation of the D to its upper fifth/lower fourth A. First, the slowing of the harmonic rhythm at m. 26 allows our ears to sit on the D major sound momentarily and give a chance to break away from an F♯minor context. Second, the repeated anacrusic rhythm of the melody in mm. 30–31 creates momentum that propels the music—including the voice-leading and harmony—forward; thus the C♮ of m. 30 and the B of m. 31 are more convincingly participating in a fourth progression because of the forward momentum of the top voice.

As shown most clearly in Examples 3a and b, my large scale interpretation of the first half of the piece treats the F♯minor section as an upper third of D (with the voice on D moving down by step, a Leittonweschel) and the G major section as the structural predominant, a lower neighbor to the structural dominant A, which arrives in m. 42. This allows for a melodic (and Classical, with a capital ‘C’) bass: ^1–^3–^4–^5–^1. If Mozart wrote this piece, it would probably support the cadential progression I–I6–II6/5–V6/4–V7–I but here, ^1–^3–^4–^5–^1 supports I–III–IV–V7–I. The most striking aspect of this (which, again, speaks to the sometimes counterintuitive nature of Schenkerian readings) is the role of F♯. When we listen to or perform this piece, I think few of us are thinking “O.K., I’m really composing out D major by prolonging its upper third with one voice lowered by step” from mm. 16–26. Rather, I think most of us would just say “I’m in F♯minor right now, cool.” But Schenkerian analysis demands hierarchical relegation within a diatonic framework. And if we do take F♯as the upper third of D, then it is the amount of temporal and tonal emphasis given to that F♯that is striking. This knowledge might suggest that a performer could play more tentatively from mm. 16–26, walking on eggshells instead of breathing Austrian countryside air like you might in mm. 1–15.

SGP–June, 2019

Footnotes:

[1]Maurice J.E. Brown, Eric Sams, and Robert Winter, “Schubert, Franz,” Grove Music Online (2001), accessed 29 May, 2019, https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000025109.

[2]Ibid.

[3]Jerry Dubins, “Schubert: Piano Trio in E♭, op. 100. Piano Sonata in A, op. 120 (D. 664),” Fanfare 34, no. 5 (May–June, 2011), 392–3.

[4]Willian Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

[5]See Milton Babbitt, The Collected Essays of Milton Babbitt, ed. Stephen Dembski, Andrew Mead, and Joseph N. Straus (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011) and Joseph N. Straus, “Babbitt the Analyst,” Music Theory Spectrum 34, no. 1 (Spring, 2012), 26–33.