Analytical Vignette #2

What does "a proto-hip-hop beat" sound like?

Unpacking Bob Stanley's (2013) stylistic descriptions

Example 1: The Rolling Stones, "Honky Tonk Women" (0:00–0:17)

Example 1: The Rolling Stones, "Honky Tonk Women" (0:00–0:17)

1. Introduction

I've been preparing for my doctoral program's "Second Exam"–the name we give to our comprehensive exams–which I will probably attempt in early Fall 2020. Of the four essays we are required to write over the course of two days in twelve hours, one of them is a "repertoire" question that usually asks you to trace the history and musical development of a given genre over a given period of time in a couple geographic areas. 20th- and 21st-century popular music is fair game on the Second Exam, so I've been reading Bob Stanley's 2013 history of popular music Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! The Story of Pop Music from Bill Haley to Beyoncé in preparation [1]. It's a long read (552 pages of text) and Stanley flies through names, songs, dates, and Billboard chart data. I really wish I could take more time with it because virtually every page is rich with observations about changes in musical style, evaluations of creative effectiveness, fascinating biographical accounts, and stories of various lines of influence. Alas, I have a lot more reading and repertoire to cover, so my reading of Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! will be relatively rushed.

But I do at least want to take some time to expand upon a few of my favorite moments from Stanley's book. The idea came to me as I read an interesting quote from a passage where Stanley is discussing the Rolling Stones and Hard Rock. Stanely writes, "the louche 'Honky Tonk Woman' (no. 1, '69) featured a proto-hip hop beat and found [the Rolling Stones] back on familiar territory, in the arms of a bevy of women" (196). What is Stanley picking up on from the sounds of the music itself that causes him to make such a claim? What are the sonic features that lead him to draw connections between, say, Humphrey Lyttelton's "Bad Penny Blues" (1956) and the Beatles' "Lady Madonna" (1968)? Is it possible to discern what he means–musically speaking–when he makes such colorful descriptions as "the only safe way to play folk songs in the United States was by frying them, tossing them, and coating them in sugar" (115)?[2] Don't get me wrong, Stanley's book is a huge achievement for popular music studies and I will probably envy his knowledge of the landscape of pop/rock music for the rest of my life. But, for a music theorist, some of his use of technical jargon (e.g., when he discusses songs from Madonna's album Erotica, he says, "Other singles from the album ('Rain,' 'Deeper and Deeper,' 'Bad Girl') were good solid disco pop, based around minor chords" (422, emphasis added)) is underbaked.

In this analytical vignette, I unpack three quotes in which Stanley is either describing influence of one song/artist to another or describing some aspect(s) of a song using language that is vivid and effective but not necessarily understandable by musicians more fluent in the terminology of Classical music/standard music notation. The point of this essay is twofold. On the one hand, I'm practicing my own "interpreting what authors are saying" skills (I like to call this "scholarly mind-reading"; standardized tests would probably just call it "reading comprehension"). And on the other hand, I'm creating a supplement to Stanley's book by bringing my taste for transcription, analysis, and specific music theory terminology to the table to add another dimension to his excellent work.

2. What does "a proto-hip hop beat" sound like?

Before we even get to transcription, a couple problems with Stanley's quote need to be addressed. First, what exactly is he referring to by "the beat"? Is he talking about the pattern of the drums only? The entire percussion pattern (drums plus a cowbell which is heard throughout the song)? Or perhaps does he just generally mean "the groove" (all the rhythmic an articulative elements combined, from drums, cowbell, rhythm guitar, vocal delivery, etc.) of the song as a whole? Stanley doesn't specify, so we can't know for sure. But let's just make an educated guess: usually when people describe the "beat" of a song, they are talking about the repeating patterns of the drums and percussion. Second, it's kind of an oxymoron to say something is a "hip-hop beat" in the first place since hip-hop's central creative process involves sampling, i.e., borrowing from previous recordings to comprise its non-rapped material.[3] Thus, "hip-hop" beats are most often actually "funk beats" or "rock & roll beats." Perhaps Stanley could have rephrased the quote in question along these lines: "The louche 'Honky Tonk Women' (no. 1 '69) featured a drum and percussion pattern similar to those that would catch the ears of early hip-hop producers."

Enough hairsplitting, let's get to some music. Example 1 shows a transcription of the opening bars of "Honky Tonk Women." The song opens with a solo cowbell, at which point the metrical orientation (where the downbeat of the probably 4/4 time signature is) is not totally clear, although it doesn't take too long to reveal itself. Near the end of the cowbell's second time through its pattern (short–long–short–long–long), the drum set enters with a pickup. It's a standard rock beat with hit hat strokes on every eighth note, and the kick drum (Beats 1 and 3) and snare drum (beats 2 and 4) essentially alternating, providing the backbeat standard to a number of popular genres (rock, jazz, hip-hop, even reggae and ska). The kick drum does not actually sound on beat 3, but it is struck on the "and" of 3, a delay which gives more snap and intensity to the beat-4 snare stroke. Stanley's definitely correct in drawing a correspondence between this basic percussion pattern and the type of beat that an early hip-hop group like Sugarhill Gang, Run-D.M.C., or Kurtis blow would be interested in sampling. In fact, according to whosampled.com, the very Rolling Stones song that Stanley claims features a "proto-hip-hop beat" has been sampled in twenty-one actual hip-hop songs![4] Notably, Kid Rock sampled it in a 1990 track "The Upside," and Public Enemy used it their song "Honkey Tonk Rules" from 2015.

As a point of comparison, take the famous collaborative track "Walk This Way" by Run-D.M.C. featuring Aerosmith. The opening build up of this song is shown in Example 2. The percussion/drum patterns in this song and "Honky Tonk Women" share several musical features. "Walk This Way" once again features steady eighth-note pulsing hit-hat hits and kick drum-snare drum alternation on the odd- and even-numbered beats of the measure, respectively. The kick drum in "Walk This Way" actually sounds on beat 3, and this strike is also surrounded by an anticipation and and after stroke on the "and" of beat 3 (just like in "Honky Tonk Women," although there, the "and of 3" kick drum sounded more like a pickup to the beat-4 snare, whereas in "Walk This Way," it sounds like an afterthought to the beat-3 kick).

I've been preparing for my doctoral program's "Second Exam"–the name we give to our comprehensive exams–which I will probably attempt in early Fall 2020. Of the four essays we are required to write over the course of two days in twelve hours, one of them is a "repertoire" question that usually asks you to trace the history and musical development of a given genre over a given period of time in a couple geographic areas. 20th- and 21st-century popular music is fair game on the Second Exam, so I've been reading Bob Stanley's 2013 history of popular music Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! The Story of Pop Music from Bill Haley to Beyoncé in preparation [1]. It's a long read (552 pages of text) and Stanley flies through names, songs, dates, and Billboard chart data. I really wish I could take more time with it because virtually every page is rich with observations about changes in musical style, evaluations of creative effectiveness, fascinating biographical accounts, and stories of various lines of influence. Alas, I have a lot more reading and repertoire to cover, so my reading of Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! will be relatively rushed.

But I do at least want to take some time to expand upon a few of my favorite moments from Stanley's book. The idea came to me as I read an interesting quote from a passage where Stanley is discussing the Rolling Stones and Hard Rock. Stanely writes, "the louche 'Honky Tonk Woman' (no. 1, '69) featured a proto-hip hop beat and found [the Rolling Stones] back on familiar territory, in the arms of a bevy of women" (196). What is Stanley picking up on from the sounds of the music itself that causes him to make such a claim? What are the sonic features that lead him to draw connections between, say, Humphrey Lyttelton's "Bad Penny Blues" (1956) and the Beatles' "Lady Madonna" (1968)? Is it possible to discern what he means–musically speaking–when he makes such colorful descriptions as "the only safe way to play folk songs in the United States was by frying them, tossing them, and coating them in sugar" (115)?[2] Don't get me wrong, Stanley's book is a huge achievement for popular music studies and I will probably envy his knowledge of the landscape of pop/rock music for the rest of my life. But, for a music theorist, some of his use of technical jargon (e.g., when he discusses songs from Madonna's album Erotica, he says, "Other singles from the album ('Rain,' 'Deeper and Deeper,' 'Bad Girl') were good solid disco pop, based around minor chords" (422, emphasis added)) is underbaked.

In this analytical vignette, I unpack three quotes in which Stanley is either describing influence of one song/artist to another or describing some aspect(s) of a song using language that is vivid and effective but not necessarily understandable by musicians more fluent in the terminology of Classical music/standard music notation. The point of this essay is twofold. On the one hand, I'm practicing my own "interpreting what authors are saying" skills (I like to call this "scholarly mind-reading"; standardized tests would probably just call it "reading comprehension"). And on the other hand, I'm creating a supplement to Stanley's book by bringing my taste for transcription, analysis, and specific music theory terminology to the table to add another dimension to his excellent work.

2. What does "a proto-hip hop beat" sound like?

Before we even get to transcription, a couple problems with Stanley's quote need to be addressed. First, what exactly is he referring to by "the beat"? Is he talking about the pattern of the drums only? The entire percussion pattern (drums plus a cowbell which is heard throughout the song)? Or perhaps does he just generally mean "the groove" (all the rhythmic an articulative elements combined, from drums, cowbell, rhythm guitar, vocal delivery, etc.) of the song as a whole? Stanley doesn't specify, so we can't know for sure. But let's just make an educated guess: usually when people describe the "beat" of a song, they are talking about the repeating patterns of the drums and percussion. Second, it's kind of an oxymoron to say something is a "hip-hop beat" in the first place since hip-hop's central creative process involves sampling, i.e., borrowing from previous recordings to comprise its non-rapped material.[3] Thus, "hip-hop" beats are most often actually "funk beats" or "rock & roll beats." Perhaps Stanley could have rephrased the quote in question along these lines: "The louche 'Honky Tonk Women' (no. 1 '69) featured a drum and percussion pattern similar to those that would catch the ears of early hip-hop producers."

Enough hairsplitting, let's get to some music. Example 1 shows a transcription of the opening bars of "Honky Tonk Women." The song opens with a solo cowbell, at which point the metrical orientation (where the downbeat of the probably 4/4 time signature is) is not totally clear, although it doesn't take too long to reveal itself. Near the end of the cowbell's second time through its pattern (short–long–short–long–long), the drum set enters with a pickup. It's a standard rock beat with hit hat strokes on every eighth note, and the kick drum (Beats 1 and 3) and snare drum (beats 2 and 4) essentially alternating, providing the backbeat standard to a number of popular genres (rock, jazz, hip-hop, even reggae and ska). The kick drum does not actually sound on beat 3, but it is struck on the "and" of 3, a delay which gives more snap and intensity to the beat-4 snare stroke. Stanley's definitely correct in drawing a correspondence between this basic percussion pattern and the type of beat that an early hip-hop group like Sugarhill Gang, Run-D.M.C., or Kurtis blow would be interested in sampling. In fact, according to whosampled.com, the very Rolling Stones song that Stanley claims features a "proto-hip-hop beat" has been sampled in twenty-one actual hip-hop songs![4] Notably, Kid Rock sampled it in a 1990 track "The Upside," and Public Enemy used it their song "Honkey Tonk Rules" from 2015.

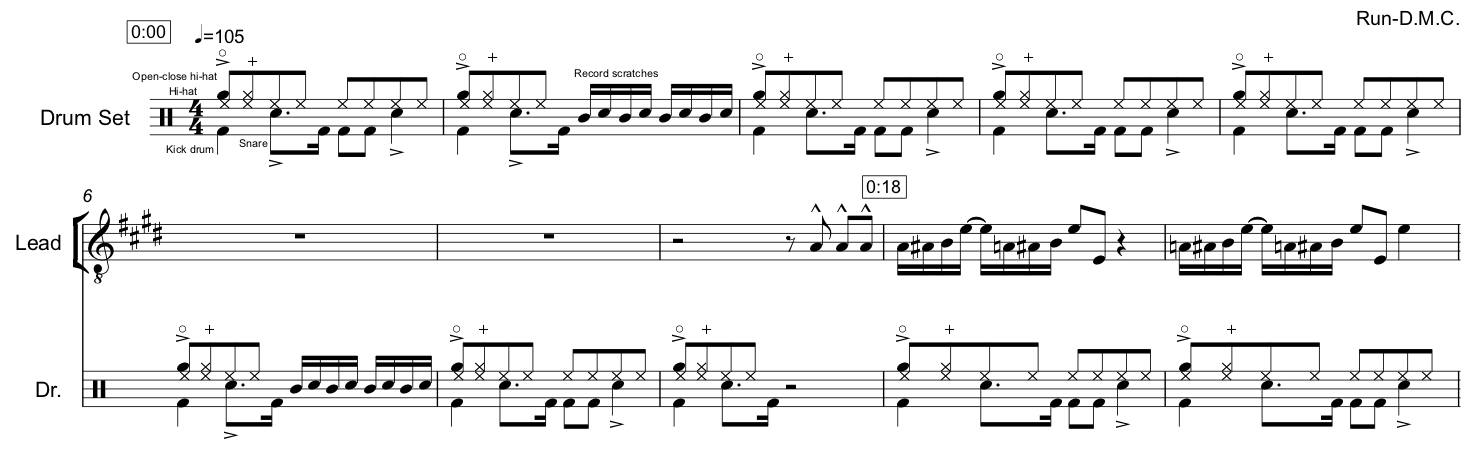

As a point of comparison, take the famous collaborative track "Walk This Way" by Run-D.M.C. featuring Aerosmith. The opening build up of this song is shown in Example 2. The percussion/drum patterns in this song and "Honky Tonk Women" share several musical features. "Walk This Way" once again features steady eighth-note pulsing hit-hat hits and kick drum-snare drum alternation on the odd- and even-numbered beats of the measure, respectively. The kick drum in "Walk This Way" actually sounds on beat 3, and this strike is also surrounded by an anticipation and and after stroke on the "and" of beat 3 (just like in "Honky Tonk Women," although there, the "and of 3" kick drum sounded more like a pickup to the beat-4 snare, whereas in "Walk This Way," it sounds like an afterthought to the beat-3 kick).

Example 2: "Walk This Way" by Run-D.M.C. featuring Aerosmith (1986) (0:00–0:25)

Example 2: "Walk This Way" by Run-D.M.C. featuring Aerosmith (1986) (0:00–0:25)

Yet the beat in "Walk This Way" uses quite a different timbral palette than "Honky Tonk Women." Timbre can't be displayed very well in music notation, but suffice it to say that the Run-D.M.C. track uses electronic/processed sounds while it seems that almost everything on "Honky Tonk Women" was recorded live.

3.

4.

5. Conclusion

3.

4.

5. Conclusion

Footnotes:

[1] Bob Stanely, Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! The Story of Pop Music from Bill Haley to Beyoncé (New York: Norton, 2014). I would be remiss if I did not make a few remarks on the term "pop." Put simply, "pop"/"popular" is a very messy term that probably means something different to everyone. Other than picking up on what Stanley thinks "pop" is implicitly from the repertoire he chooses to discuss and the way he chooses to discuss it, he does give a brief discussion of what it means to him in his Introduction (pp. xii–xv). Writes Stanley, "What exactly is pop? For me, it includes rock, R&B, soul, hip hop, house, techno, metal, and country. If you make records, singles and albums, and if you go on TV or on tour to promote them, you're in the pop business. If you sing a cappella folk songs in a suburban pub, you're not. Pop needs an audience that the artist doesn't know personally–it has to be transferable" (xii). I appreciate Stanley's quasi-academic approach to defining pop; he is clear about what he means but is not afraid to support his definition with personal anecdote, instead of having to plunge into a lengthy philosophical discussion of what pop means. The only quibble I would have with Stanley is that he never explicitly acknowledges that he mostly leaves out pop music traditions from outside the U.S. and the U.K. He does bring up musical activity in Australia, Canada, and continental Europe from time to time, but he never says that what he is leaving out is home-grown popular traditions from many other regions of the world (take, for example, high life or hip life in Ghana). I do not fault Stanley for choosing to write a book that focuses on specific regions, peoples, cultures, and dates; no one should attempt to write a history of the entire globe's pop music from all time periods. But his lack of acknowledgement of who is left out of the picture in this book makes the Anglo-Americaness of pop seem like it happened in a bit of a bubble.

[2] In case anyone is interested, Stanley cites the following three songs of this sort of disguised American folk pop style: "Banana Boat Song" (1957) by Harry Belafonte, "Tom Dooley" (1958) by the Kingston Trio," and "Green Fields" (1960) by the Brothers Four.

[3] For the sake of argument, I'm excluding hip-hop producer's use of drum machines, which has surely been a compositional option since close to hip-hop's founding in the early 1970's. Of course, hundreds, if not thousands, of hip-hop tracks have "beats" (i.e., drum patterns) that were made in a studio fresh for that song. But sampling is the original means of hip-hop production and closer to the genre's core definition.

[4] Search results on whosampled.com can be seen here: www.whosampled.com/The-Rolling-Stones/Honky-Tonk-Women/

[1] Bob Stanely, Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! The Story of Pop Music from Bill Haley to Beyoncé (New York: Norton, 2014). I would be remiss if I did not make a few remarks on the term "pop." Put simply, "pop"/"popular" is a very messy term that probably means something different to everyone. Other than picking up on what Stanley thinks "pop" is implicitly from the repertoire he chooses to discuss and the way he chooses to discuss it, he does give a brief discussion of what it means to him in his Introduction (pp. xii–xv). Writes Stanley, "What exactly is pop? For me, it includes rock, R&B, soul, hip hop, house, techno, metal, and country. If you make records, singles and albums, and if you go on TV or on tour to promote them, you're in the pop business. If you sing a cappella folk songs in a suburban pub, you're not. Pop needs an audience that the artist doesn't know personally–it has to be transferable" (xii). I appreciate Stanley's quasi-academic approach to defining pop; he is clear about what he means but is not afraid to support his definition with personal anecdote, instead of having to plunge into a lengthy philosophical discussion of what pop means. The only quibble I would have with Stanley is that he never explicitly acknowledges that he mostly leaves out pop music traditions from outside the U.S. and the U.K. He does bring up musical activity in Australia, Canada, and continental Europe from time to time, but he never says that what he is leaving out is home-grown popular traditions from many other regions of the world (take, for example, high life or hip life in Ghana). I do not fault Stanley for choosing to write a book that focuses on specific regions, peoples, cultures, and dates; no one should attempt to write a history of the entire globe's pop music from all time periods. But his lack of acknowledgement of who is left out of the picture in this book makes the Anglo-Americaness of pop seem like it happened in a bit of a bubble.

[2] In case anyone is interested, Stanley cites the following three songs of this sort of disguised American folk pop style: "Banana Boat Song" (1957) by Harry Belafonte, "Tom Dooley" (1958) by the Kingston Trio," and "Green Fields" (1960) by the Brothers Four.

[3] For the sake of argument, I'm excluding hip-hop producer's use of drum machines, which has surely been a compositional option since close to hip-hop's founding in the early 1970's. Of course, hundreds, if not thousands, of hip-hop tracks have "beats" (i.e., drum patterns) that were made in a studio fresh for that song. But sampling is the original means of hip-hop production and closer to the genre's core definition.

[4] Search results on whosampled.com can be seen here: www.whosampled.com/The-Rolling-Stones/Honky-Tonk-Women/